Subscribe to newsletter: 10% OFF

Sign up to receive 10% off your order as well as the latest updates on new arrivals, exclusive promotions and events.

Alice Neel, Mother and Child, 1982

Claude Monet, Camille Monet and a child in the Artist's Garden in Argenteuil, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 1875

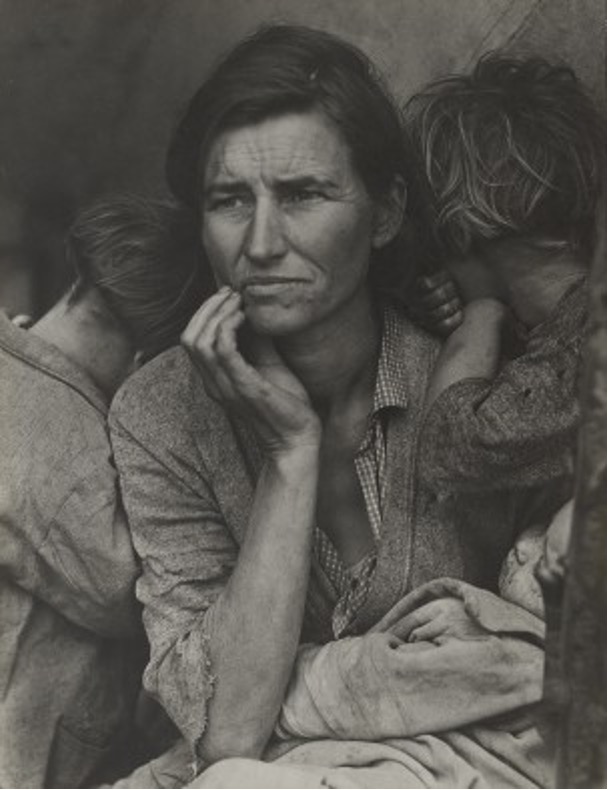

Dorothea Lange, Migrant Mother, 1936

Amy Sherald, Mother and Child, 2016

Elisabeth Louise Vigee Le Brun, Self Portrait With Her Daughter Julie, 1789

LaToya Ruby Frazier, Momme, 2008

Mary Cassatt, Breakfast in bed, 1897

James McNeill Whistler, Arrangement in Grey and Black No.1 (Whistler’s Mother), 1871

Berthe Morisot, The cradle, 1872

From Renaissance to the Contemporary: Celebrating Mothers in Art

By Louise Oliphant, Contemporary Art BA (Hons), International Journalism MA

Whilst mothers creating artwork still seems a tactical struggle in artworld discourses, those who do combine the often-subverted categories make sure to celebrate motherhood and all that it involves. As such, mothers in art or the theme of motherhood has been commonly canonised and idealised over centuries in the art domain. And rightly so, where women were often banished from the title of one of the ‘greats’ -noting critic Linda Nochlin’s (1971) ‘Why have there been no great women artists?’- women were often deemed too preoccupied with parenthood to create artworks of real skill and talent. Whilst this sounds highly illogical, we nonetheless must recognise the restrictive nature, or strategic management of both the public and private sphere that women mothers in art have had to endure. And so, despite the limited history of mother artists, there were great female pioneering painters that proved assumptions wrong and thus deserve a celebration, if not every day, then especially on Mother’s Day.

From the Renaissance period, where Elizabeth Vigée Le Brun (1786) painted images appraising the beloved bond between mother and child and modern photography, where Dorothy Lange’s (1936) Migrant mother situated a mother’s care within cultural and political contexts, to the contemporary where Alice Neil (1982) pictures a more authentic truth to the tiresome first years of parenthood, the portrayal of mothers and their children remains entirely emotive, sensitively intimate and simply captivating. Perhaps disregarding Louise Bourgeois’ (1999) Maman the mother here, for its conceptualised spider installation takes an uncomfortable, more nuanced representation of motherhood, let say. Still, as we can see, where society has evolved, as has the art world, modernising the depiction of women and mothers both in art and real life. With the binary dichotomy of mother and artist now at rest, women have emerged as artists in their own right and throughout the timeline of art movements, motherhood has remained a constant inspiration. This stands no matter the gender or status, as childless artists and men have joined the celebration, consistently painting portraits of their female forbearers; demonstrated through Claude Monet’s (1875) Camille Monet and a Child in the Artist’s Garden in Argenteuil or more famously in James McNeill’s (1971), Whistler’s Mother.

Yet, Mary Cassatt remains the most renowned in her paintings that spotlight the slightly mundane relationship between mother and daughter and is most notable in her ability to construct the modern woman in a female space that seems ultimately revolutionary. The normative, not particularly extravagant imagery of women and children experiencing daily tasks reconstructs the private sphere through an appreciation and value of what might otherwise have been taken for granted. From the ritual of bathing to eating breakfast in bed, Cassatt makes the private life public, mirroring the second-wave feminist argument of ‘the personal is the political’ to give back a sense of control and power to women mothers. Her 1897 oil painting ‘Breakfast in bed’ proves exemplary of this; a poised child having crawled into her mother’s bed is embraced within her arms, as the mother herself seems tired, exhausted almost. But through a detailed softness in painting technique, semiotics of love and devotion cannot go unmissed. Cassatt here premises on the reality, depicting the areas of motherhood that are not always glamourous or full of energy and joy, but inflicts a significance to the ordinary in idealising the ability of a mother, her strength and commitment. This prominence is further enhanced through the familiarity of the dominant unit of mother and child that encapsulates all of her paintings. The dominance here rests in the foreground, where compositionally both figures fill entire paintings, as though they are cropped or close-up. As viewers, we are placed at eye-level, propelling the rest of the room out of sight and so out of mind; the relationship between mother and child becomes blissfully overwhelming and intensely intimate. In many ways this reinforces a mother’s control over female space, one that we cannot see and so remains entirely hers. Cleverly, Cassatt is able to showcase the potentially acquainted private sphere of the home, where parenthood is at its most dutiful with gratitude and worth whilst maintaining a respectability to what is ‘private’. By doing so, she does not expose the mother in response to her given title but instead advocates a noticeability to all that mothers do for their children.

In providing an iconicity to motherhood, Mary Cassatt, among others compel an immense appreciation for not just one mother, but for all mothers. If these artworks don’t inspire a devotion to motherhood then what will?

Happy Mother’s Day from the team at Labeca.

Sources:

https://www.radford.edu/rbarris/Women%20and%20art/amerwom05/marycassatt.html

https://feltmagnet.com/painting/Mothers-in-Art-Some-Mothers-Day-Paintings-and-Pictures

https://news.artnet.com/art-world/mothers-in-art-history-1832367

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=toBtmsTkw4k

https://www.ifitshipitshere.com/paintings-of-mom-by-33-famous-artists-for-mothers-day/